I made a promise a while back after watching her heartbreaking performance (as second female lead) in the Netflix special First Love that I’ll check out more of Indo Kaho’s work – and I make good on all my promises. Almost immediately I sat myself down and saw Blue Hour (2019, dir. Hakota Yuko), and this time Kaho is center stage. Although coming two years before First Love, somehow she looks much older, more disenchanted in this film. From the first scene (a young child running through a seemingly endless rice field in the dim, blue hour of morning, and then cut to: Kaho sleepless at a hotel after an extramarital fling), Blue Hour sets the tone for the next ninety minutes: melancholic and quiet… very, very quiet.

Kaho plays Sunada, a thirty year old director of commercial advertisements (interestingly enough, director Hakota is herself a commercial director, with this film making for her theatrical debut) with a go-getter, demanding personality. When we meet her, she’s on the way to make a brief visit to her hometown all the way in the Japanese countryside (the “boonies”, in her words) to visit her ailing grandmother. Accompanying her on this trip is her best friend Asami (Shim Eun-Kyung).

I love a good road trip movie. Within Japanese filmography, this typically means a passage by train, boat, or road across expansive sceneries: wide angle shots of sprawling temples and colorful torii gates, Mount Fuji peeking through the airplane-like windows of a shinkansen hurtling through quiet villages. Blue Hour gives us none of that, and it it plays well into Sunada’s no-nonsense personality. She’s not going out for a vacation: it’s a calculated act, meant to pay her societal obligations and nothing more. As she constantly reminds Asami: she’ll stop by her family’s house, pay a visit to grandma, and then get back on the road.

The supposedly short visit is sabotaged when a typhoon strands them in the Sunada household. Her father, probably growing senile, has taken to buying up an expansive collection of useless antiques, including an actual samurai sword. Her brother teaches at a local middle school, but appears to be something of a creep. Her mother no longer cooks meals for the household because nobody eats them anymore: instead, she’s stocked up the fridge and pantry with an endless supply of convenience store onigiri and instant noodles.

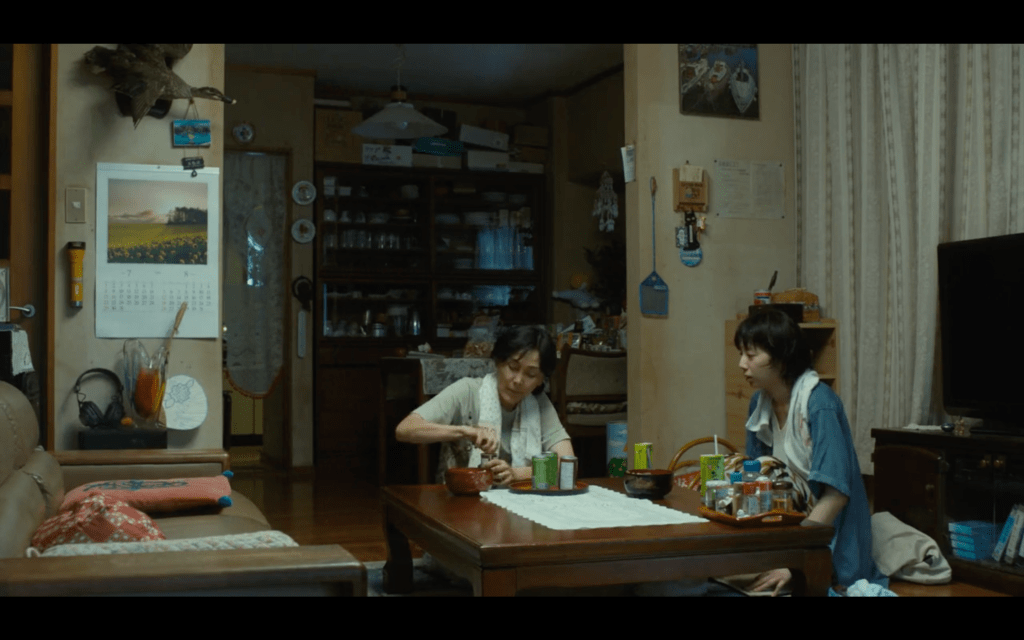

If that had been all, this trip might have ended up as another overnight feat of tolerance, no different from her quiet tolerance of her marital unhappiness, or her growing dissatisfaction at work. But with happy-go-lucky Asami beside her, we watch Sunada slowly come to question exactly what it is she’s keeping at a distance. This plays out in one potent scene the morning after they are rained in, when Sunada wakes up to find Asami already in the dining room, heartily enjoying a breakfast prepared by her mother (who supposedly has stopped cooking).

Rhythm-wise, the film is beautifully laid out. The narrative unfolds as if in a spiral, representing Sunada’s own circuitous path towards acceptance. The film feels surefooted where its character is ever-hesitant. Maybe even to a fault: really the only detriment to the story is its strong adherence to this structure, and towards its close feels about as distanced as its heroine. Has Sunada found empowerment in her opening up, or has she merely resigned to her place in this entangled social web? We don’t know. And though she spends the rest of the drive back laughing with Asami, we wonder if she won’t be back to her old self by the time they reach the city.

Leave a comment